As we continue this series, it’s important to ground our reflections in the science of learning and brain research. Teachers make daily instructional decisions that research can illuminate but not fully prescribe. What neuroscience and educational science show us are principles that help explain how students learn best and how certain practices support long-term understanding. Previous post

Active Retrieval Is More Powerful Than Passive Re-Exposure

Cognitive psychology has consistently found that retrieval practice, that is, actively bringing information to mind, deepens learning more than simply re-reading or re-exposure. Research spanning laboratory and classroom settings shows that engaging students in retrieval (quizzing, explaining, recall exercises) leads to better long-term memory retention than repeated study or review alone. (source 1, Source 2)

This is often referred to as the testing effect or retrieval practice effect. The retrieval practice effect is an effective strategy for combating the Ebbinghaus Effect, aka the Forgetting Curve. While it is sometimes misinterpreted as “more tests,” it is really about effortful recall, getting students to retrieve and rethink information. It’s retrieval itself, not just repetition, that strengthens memory traces.

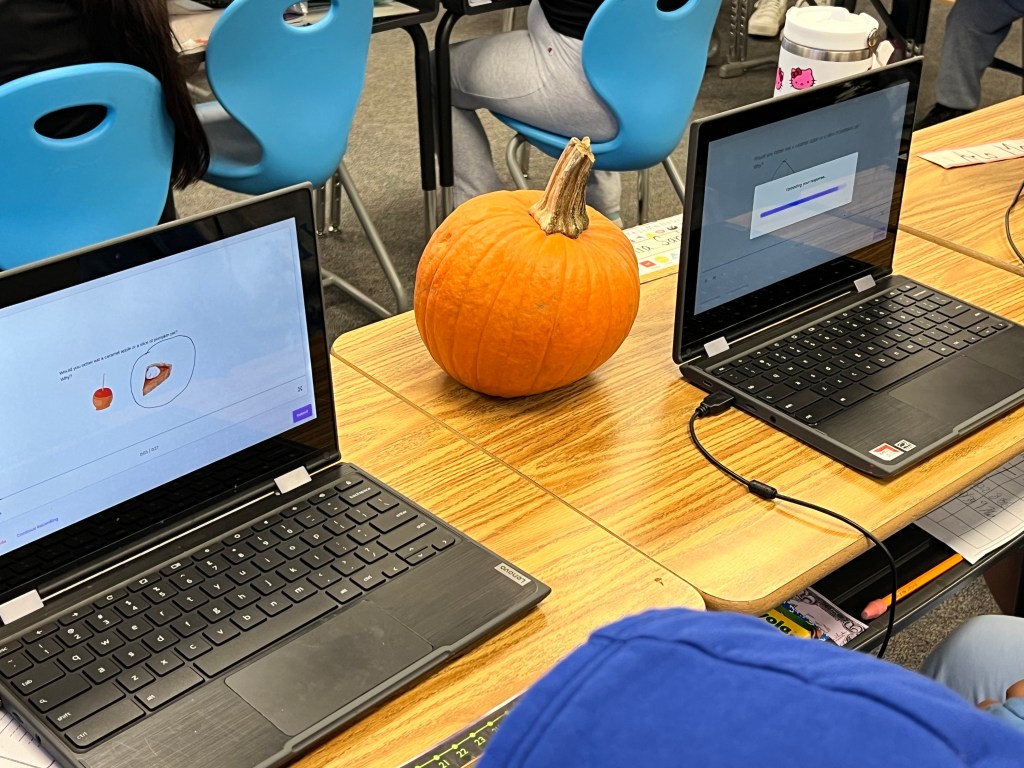

In other words, this means that asking students to produce explanations, to summarize in their own words, or to write and discuss thinking aloud builds deeper learning than simply having them repeatedly read material or answer DOK 1-type questions. This aligns closely with production-based approaches like #MathReps and #EduProtocols, which encourage students to reveal their thinking rather than simply select answers.

Cognitive Load Matters Both With and Without Screens

Science also reminds us that our brains have limited working memory capacity. Cognitive Load Theory explains that when students are overwhelmed with too much information or poorly structured tasks, learning suffers. This is why #EduProtocols recommends starting with a fun, low-cognitive load (non-academic) subject when introducing a new protocol.

Some research on multimedia learning, how information is presented with visuals, audio, and text, suggests that poorly designed digital content can increase cognitive load, making it harder for students to focus on what matters.

Importantly, cognitive load is not caused by screens themselves, but by how information is presented and how much unrelated or distracting material competes for attention. Even when we don’t use technology, we have all experienced cognitive overload from information, especially when it is new or ‘meaty’. This is why it is important to use well-designed tasks that chunk information, reduce unnecessary complexity, and scaffold thinking, helping students allocate mental energy to deep learning, whether on paper or on a device.

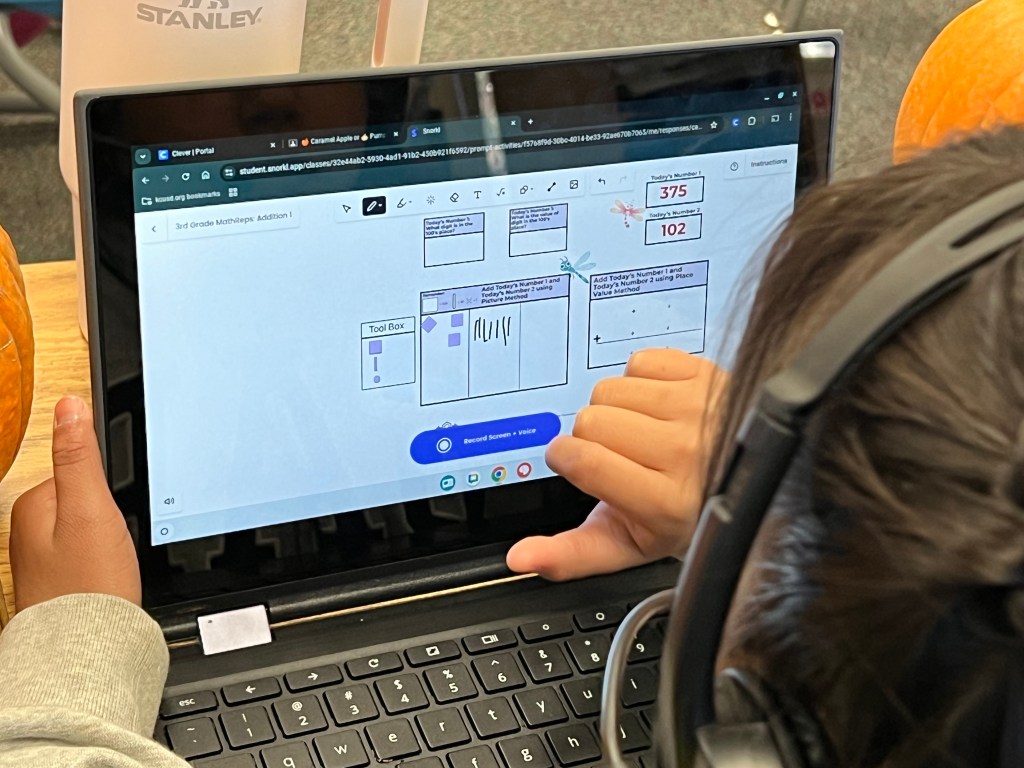

This is where tech can help: platforms that analyze student errors, present information in multiple representations, or guide students through step-by-step reasoning can reduce unnecessary load and help students focus on what matters most. Tools like Snorkl and Wayground (which provide instant feedback and class-wide analysis) can lighten the teacher’s load while still requiring students to produce and explain their thinking. This isn’t to say that the use of technology is better. If a teacher needs to learn a platform to lighten their load, it can lead to cognitive overload; that’s not good either.

It’s about balance for both students and teachers.

Explanation Strengthens Learning Across Contexts

Research and classroom evidence agree upon a central idea: students learn better when they must explain their thinking. This is true whether explanations are verbal, written, visual, or recorded. Explanation forces students to organize, articulate, and refine their understanding, something that passive or consumption tasks rarely do.

This finding is supported by the English Language Development (ELD) standards, which highlight explanation as crucial for language learners; I would argue the same holds for all students. The act of explaining requires higher-order thinking, connecting ideas, making meaning, and justifying reasoning, and is linked to stronger understanding across domains. We know that if a student can accurately explain their thinking, they understand the concept. And if, while they explain their thinking, they have a misconception, we, as teachers, can address the issue immediately.

Whether students are explaining mathematical reasoning, composing a paragraph, or teaching a peer through a screencast, the cognitive work of explanation activates deeper learning processes.

What Neuroscience Says About Screen Use

Neuroscience research and cognitive development studies paint a layered picture of screen use, especially in early childhood and developing brains. As teachers, we have all seen our fair share of young children passively watching something on a phone or tablet. I have my own personal thoughts on that.

Some findings suggest that excessive screen time, especially passive, unstructured exposure, can be associated with reduced development of executive functions (such as working memory, inhibitory control, and attentional networks) and changes in brain connectivity during critical developmental periods. (Source 3) Other work points out that heavy screen exposure in young children can replace activities like conversation, play, and social interaction that are essential for the development of attention, language, and executive skills. (Source 4)

I will acknowledge the limits of this research:

- Most studies on screen use and brain development focus on quantity and context of use, not technology per se.

- Research does not support simplistic claims that screens alone “ruin attention” or permanently damage cognition; effects depend heavily on the type of engagement, content quality, and context. (Source 5)

- There is no consensus that screens are inherently worse for learning than other media; rather, the design of tasks and interactions matters most. I would be curious to see any studies on the effects of social media on attention spans, how they relate to perseverance and productive struggle.

Screens can be part of effective learning when they prompt students to think, produce, interact, and explain, not just watch or click. I still advocate for common sense. Personally, I don’t think plunking students down in front of a computer for extended periods of time every day is healthy.

What Research Doesn’t Claim

As educators, we must be careful not to overinterpret research into simple slogans like “technology is harmful” or “screens destroy brains.” The science shows that how we use technology matters far more than whether it exists in the classroom.

Studies on cognitive load don’t condemn all digital tools. They simply remind us that well-designed tasks that minimize the load and maximize meaningful engagement lead to better outcomes.

It’s all about balance.

What This Means for Classrooms

The science of learning supports production-based work, tasks that get students to retrieve, organize, and explain content. It also supports varied modalities and repetitive practices, whether via paper/pencil or smart tools that help with feedback and analysis. This was discussed in the Consumption vs Production post of this series.

Here’s what teachers and leaders should keep in mind:

- Retrieval practice (active recall) strengthens long-term retention more than repeated exposure.

- Cognitive load matters: thoughtful design matters more than screens.

- Explanation builds understanding: making students’ thinking visible is powerful.

- Tech can help, but only when it supports thinking, not replaces it.

Tools like Snorkl and Wayground illustrate this well: they can provide instant feedback and class analysis, helping teachers target instruction while students practice articulation of thinking. But these tools are most effective when teachers know what they want students to produce, not just consume.

Educators deserve systems that support this deeper work—not just devices to fill time. They also need support to accomplish this successfully. Leaving teachers to figure things out on their own time isn’t an acceptable solution. Schools and districts need to invest in their teachers.

What are your thoughts on this research? What have your experiences been?

Coming Next:

Research may tell us what works, but oftentimes, teachers are left to figure out how to put it all into practice successfully. Post 4 explores what happens when pedagogy is expected without proper time, training, or systemic support.